A compelling, inclusive exhibition of art from Burning Man comes to the Oakland Museum.

FUTURISTIC, INVENTIVE, KINETIC AND INTERACTIVE art — the essence of Burning Man, the annual Labor Day fest in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert — is the subject of No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man. This traveling show, organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery, debuted on the West Coast in October, and its finale show, at the Oakland Museum of California, runs through February 16, 2020.

“It is really wonderful to bring these works home,” says OMCA curator Peggy Monahan, pointing to the many Oakland-made creations, the likes of which often are seen only at Burning Man. She has placed much of the exhibition in the museum’s hall and gardens and encouraged local artists’ studios that produced many of the pieces to offer interactive programs that bring No Spectators to life.

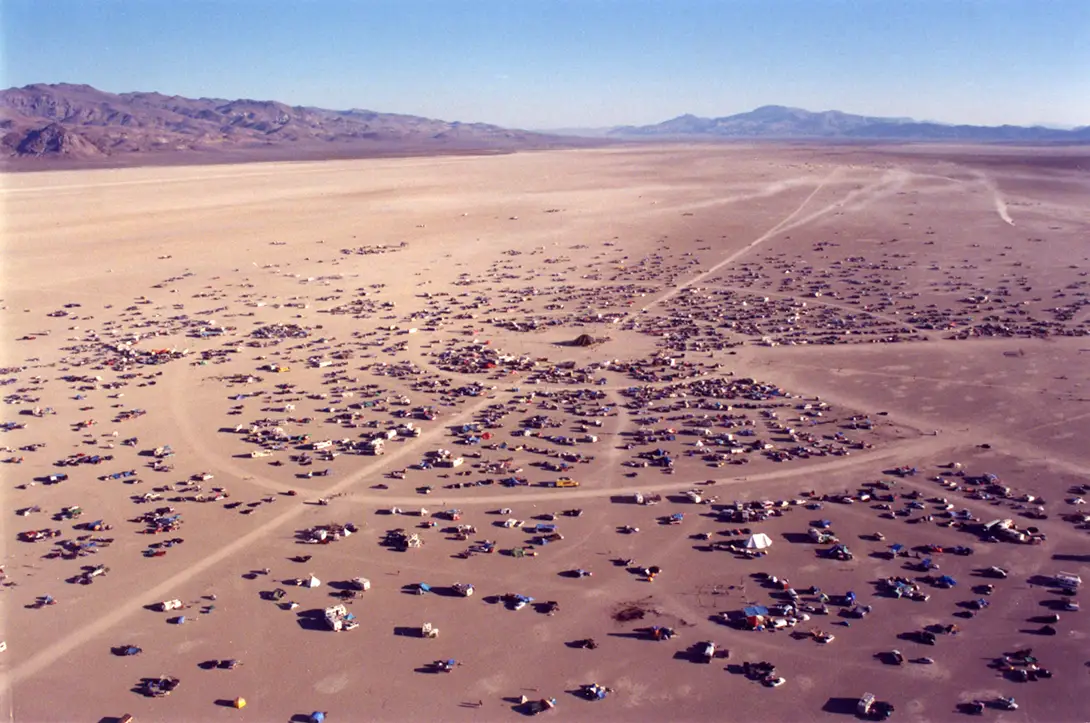

Staged on a dry lake bed 100 miles from Reno, Burning Man’s so-called Black Rock City encampment encircles a stylized effigy of a man that is burned each year at the end of the event. The extraordinary nine-day gathering of more than 70,000 people has come a long way from its origins: a convivial summer solstice bonfire on San Francisco’s Baker Beach, where a group of friends, including event founders Larry Harvey and Jerry James, burned an eight-foot driftwood figure in 1986.

That ritual began annually attracting artists, all seeking a kind of unfettered creative common space, and the burgeoning festival moved to Nevada’s desert in 1990. Since 2000, temple structures made from recycled materials by artist David Best and other volunteers have been a beloved feature. Other large artworks, crafted elsewhere and assembled on site, joined the “Man,” and fantastic bizarre cars breathing flames and belting out music began to roam Black Rock City’s open playa.

In this enormous madcap “gallery” the stylized Man also grew in size — sometimes higher than 100 feet tall.

Over time, the original free-spirited bohemian participants of Burning Man have been joined, and perhaps overshadowed by, deep-pocketed Silicon Valley tech celebrities and global media artists, but the bohemian spirit endures even in some of No Spectators’ elaborate tech-driven works.

Experimentation, collaboration and creativity infuse the more than 300 art installations that spring up at Burning Man. One of the Oakland studios behind these iconic sculptures, for instance, is the Crucible, an industrial arts education enclave that creates jewelry, costumes, paintings and even some large “mutant’” altered vehicles for the playa.

“Burning Man artists like David Best are our neighbors,” Monahan says. That’s proved an advantage. Since the temple Best created for the Renwick debut show had to remain there, OMCA was able to easily acquire a replacement: Best’s 40-foot-tall version, displayed in the museum’s garden, where people are encouraged to leave remembrances that will be saved and burned at next year’s Burning Man temple.

“Other works actually created for the playa are also exhibited out- doors here, and that made more sense,” Monahan adds. An example is East Bay artist Marco Cochrane’s 18-foot-high Truth Is Beauty, a welded-metal sculpture of a sinuous woman. It is joined by New Orleans artist Candy Chang’s famous participatory creation Before I Die — a chalkboard where people can write their top bucket-list items.

For those who want to delve deeper into Burning Man history, OMCA also presents a companion show, City of Dust: The Evolution of Burning Man, organized by the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno.

Overall, “we really tried to stay close to the Renwick Gallery’s choices,” Monahan says. That guideline, while useful, was hard to stick with, as there are many works temptingly nearby the museum could have added. Instead of doing that, she decided to involve real-life “burners” from the Bay Area as guides to the show.

“The pieces in the exhibition are the result of artists’ collectives or groups of people coming together to make art,” she points out. The museum itself already has an ongoing Burning Man kind of vibe, complete with food trucks and music on Friday nights, and “we are constantly trying to make such connections,” she says.

In that spirit of community, Monahan and her team, along with Rachel Sadd, executive director of East Bay maker-space Ace Monster Toys, added workshops for making origami cranes, necklaces and recycled-material gifts for visitors to take home. Or, perhaps, to burn?

This article originally appeared in Spaces print edition with the headline: “Burn Baby Burn”.