“I NEVER SAW myself as an artist,” San Francisco multimedia sculptor Jim Campbell says at his Dogpatch studio, pointing to artworks scattered about, including several scale models of an LED light installation he created for the 1,070-foot Salesforce Tower.

Every evening the top nine floors of the 61-story tower by Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects light up against the night sky with Campbell’s 11,136-bulb piece called “Day for Night.” Visible for miles around, it currently shows silhouettes of dancers flitting across a lit background. Clouds swirling around the building, bay life around the Exploratorium, waves crashing at Sea Cliff, Bay Area crowds and birds will all be added in time to complete this tableau of patterns of movement, captured by day and shown in a loop at night. To achieve this effect, short, injection-molded ASA (acrylonitrile styrene acrylate) plastic stems resembling a porcupine’s needles are attached to the crown of the building; on their tips are programmable LEDs, aimed inward to bounce light off the tower’s perforated aluminum crown. Shadows between the softly glowing areas of light form the silhouetted images seen from afar.

A Chicago native, Campbell is an engineer by training, with degrees in electrical engineering and mathematics from MIT. But in college he was interested in film, and he took a class on documentaries with Richard Leacock, a pioneer of cinema verité. That led to some feature filmmaking, but “I did not have the personality to be a director,” Campbell says. “I was a basket-case introvert. An MIT dysfunctional.”

Drawn inexorably to “the epicenter of everything techno- logical,” he settled happily into a 24-year stint of design engineering at Faroudja Labs in Silicon Valley, where he worked with analog circuitry and then digital technology to reduce noise in and sharpen the quality of video images. On week- ends he tinkered in his San Francisco garage-turned-studio with digital video and sculpture projects.

“I spend way too much time getting things the way I like,” Campbell says. For instance, “Day for Night,” launched in May 2018, is still a work in progress. “I have all the lousy or good characteristics of an engineer,” he adds, and perhaps persistence is one of those traits.

In 1988, having repeatedly tried to find a commercial art gallery that would show his work, he rented space along with a friend in a Tenderloin apartment for a pop-up gallery of their own.

SFMOMA curator Robert Riley, who had seen Campbell’s work at MIT, came and approved. He later included Campbell’s “Hallucination,” an interactive video installation about mental illness in which viewers seemingly set themselves ablaze, in a 1990 group show called Bay Area Media. Collector Donald Fisher snapped it up for his collection and bought another piece of Campbell’s for SFMOMA.

It was the first of Campbell’s many triumphs, but “Hallucination” was also a very personal piece: it obliquely referenced the artist’s brother who suffered from schizophrenia.

His brother’s life and eventual suicide might be seen as thematically central in Campbell’s work, which often questions what life is and what we perceive to be real. Campbell seems to suggest that external data alone is not the best descriptor. “Memories are hidden and have to be transformed to be represented,” he has said. And as art scholar Richard Shiff suggests in his essay in the book Jim Campbell: Material Light, the artist is the best filter for a truly representative image.

Riley’s affirmation and the subsequent museum and gallery recognition notwithstanding, Campbell kept his day job, and only during the last decade has he shifted fully into the realm of art.

Why did it take so long? “I grew up in a lower-middle-class suburb,” he says. “I never knew artists. That was not an option I could consider.” So he expressed his creative inner nerd through “science-based” photography and documentary-making and meanwhile stuck to a reliable engineering career. However, “what I learned at Faroudja was to work backwards from the image; to look at an image and make it look better,” Campbell reflects. To do that, he had to understand the essence of an image and how it could be viewed. “I did less and less engineering and more and more art. I started working in the realm of perception.”

Since 2000, represented by the Hosfelt Gallery in San Francisco, Campbell has shifted from conventional video imagery and home movies to figurative video images pixelated to the edge of abstraction, often by using LEDs.

In 2002, Bay Area curator Larry Rinder included Campbell in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s prestigious Biennial Exhibition in New York. Many other exhibitions followed, including several large immersive installations in darkened spaces such as one in SFMOMA’s collection called “Tilted Plane” and the haunting piece “Last Day in the Beginning of March 2003,” chronicling the last day of his brother’s life. Its random oscillating pools of light like polka dots floating against a dark background could be interpreted as lives going in and out of existence.

Gradually, as he continued to experiment with increasingly low-resolution, nearly abstract images, Campbell unwittingly started “creating work that was more saleable because it went on the wall like a painting,” he says. “It was completely counterintuitive because at work I was working on high-definition TV technology.”

He found a zone between these extremes by asking how a low-resolution image that might otherwise be considered substandard, even lifeless, could also have emotional content.

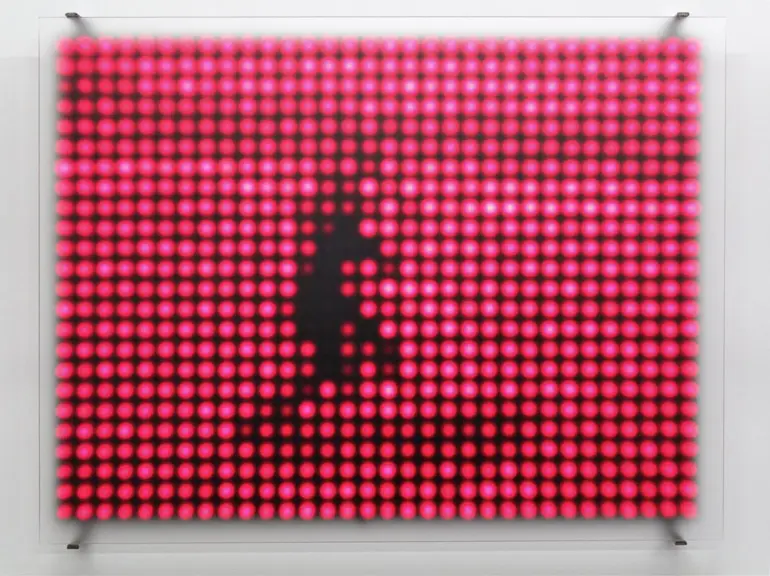

His conceptual pieces are all surprisingly low-tech. “Nothing has changed in the technology that I use. Video is video,” Campbell says matter-of-factly. The videos were translated to data and, sometimes accompanied by the rhythmic sound of heartbeats and the like, are run through computer pro- grams to activate LEDs attached to a matrix of wires. Still, instead of using existing videos, Campbell sometimes stages his material: he did so with the disabled figures walking for his “Motion and Rest” series. Or he shoots randomly as he did in New York for his “Grand Central Station” series. In “Ambiguous Icon #1 Running Falling,” a figure moving against a background of 165 red LEDs is barely discernible but, once perceived, is not easily forgotten. “That figure keeps falling,” Campbell says. “A lot of my work is about struggle,” he notes, and that is universally resonant. To fracture and abstract imagery, Campbell deploys LEDs, LCDs, projectors, TVs, customized electrical displays and video screens, often mounted behind diffusers like Plexiglas or, in some instances, machine-carved resin and glass.

A current project, at a low-income residential building at 1036 Mission Street in San Francisco, uses principles of fiber optics to project images through acrylic blocks fitted into vertical panels that flank the entrance of the building.

Campbell’s experiments with overlapping video stills to achieve abstract imagery have resulted in a series of two-dimensional backlit collages. They were made from documentary videos of political protests in New York and the 2017 Women’s March on Washington, and even when a dozen digital photographs are overlapped to achieve abstraction, the ghost of the originals is palpable.

The takeaway? An image, even a moving image, is fixed in a moment and runs in a continuous loop. Perception and memory change it and in that sense truly give it life and meaning. Perhaps, as Campbell likes to say, “The way past the image is time.”

This article originally appeared in SPACES print edition with the headline: “Moving Images”.