Obsolete purpose-built structures are morphing into versatile gathering spaces.

IN OUR TECHNOLOGICAL AGE, as brick-and-mortar businesses and institutions fade, buildings designed to house them also lose their purpose. But entrepreneurs and designers are finding ways to make them multifunctional and versatile.

Several solutions in the Bay Area, while different from each other, share one thing: they promote a sense of community. In effect, they stand in for the village square — indoor/outdoor spaces that promote interaction and relief from screen-based isolation.

IN SAN FRANCISCO, designers Yves Behar and Amir Mortazavi have revived dusty multilevel office buildings in three different neighborhoods — the Fillmore, North Beach and the Financial District — as co-working spaces called Canopy. Each spot provides stylish tech-ready desks and shareable office space, aesthetically tailored to suit its neighborhood vibe. But every Canopy is also planned as a venue for after-hours panel discussions and social events for pursuits like wine tasting, spirituality and yoga. As Mortazavi says, Canopy subscribers “can share experiences, make connections and build their networks here.”

IN MARIN, the Mill Valley Lumber Yard, an old creek-side property with red barn like structures, lay fallow for many years before new owners Matt and Jan Matthews tried, for history’s sake, to revive it in 2012. They found no lumberyard takers. So they gradually filled the buildings ringing the open space with unpretentious restaurants and flower, fashion and craft boutiques. Last summer Ged Robertson’s casual Watershed restaurant, designed by architect Chris Dorman and featuring chef Kyle Swain, opened in this thriving gathering space. It has clearly filled a need, drawing families, foodies and appreciators of music and good design.

NEAR SANTA CRUZ, Dave Allen, owner of Sonoma home furnishings store Artefact Design & Salvage, brought his design ideas to a newly formed therapeutic community called 1440 Multiversity. Its modus operandi is patterned partly after Esalen, birthplace of the human potential movement, which began in the 1960s at a former hot springs motel near Big Sur.

Multiversity also has an interesting backstory. Scott Kriens, former CEO of Sunnyvale software company Juniper Networks, and his wife, Joanie, knew Allen’s store through their interior designer Christine Janson. They wanted to do something meaningful after achieving considerable financial success.

“I grew up with a single mom and went to secondhand stores for clothes as a child,” Joanie says. “I can relate to a lot of people just getting through life, and I wanted to give others an opportunity.”

They set up a charitable granting foundation in their Saratoga home to aid social causes they care about. “I was interested in emotional learning and we wanted to make a difference in the world,” Joanie says. “Giving people a hand up and working hands-on to see them thrive — especially children with disabilities and underserved schoolchildren — was the goal.”

In 2012, as their so-called 1440 Foundation — named for the 1,440 minutes in a day — burgeoned, the Krienses needed to move their foundation office. Their search led to the defunct 75-acre Christian college campus of Bethany University in Scotts Valley, and they bought it.

With that much land available, their plans grew. The Krienses realized they also had room for something along the lines of Esalen and the “emotional learning” retreat in Massachusetts called Kripalu. “What started as a retreat center became a ‘leadership’ destination where you could learn to be the best person you want to be,” Joanie says, or find, as Scott says, “multiple paths to the discovery of self. After all,” he adds, “we are a sum of our emotional, relational and spiritual selves.”

Several of the campus’s decrepit 1950s buildings were demolished to make room for new ones. With Allen and Janson’s interior design input and help from student designer Taryne Meyer, they restored about a dozen existing houses to accommodate employees and visiting faculty. With architect Jerry Yates, they added ancillary classroom buildings and a new roughly 8,000-square- foot Japanese-temple-meets-Craftsman-home dining hall called the Kitchen Table.

Yates’ inspiration there was reportedly the lodge designed by architect Julia Morgan at Asilomar in Monterey. Inside, the dining hall showcases an arabesque-tile-covered octagonal food service counter conceived by architect Michael Guthrie, communal tables and benches that Allen fashioned from old Javanese timbers, and forged ironwork and chandeliers by metalwork artisan Jefferson Mack. Gardens with herbs for executive chef Kenny Woods’ recipes were planted alongside vegetables for a cooking-demonstration kitchen occupying one of the few stand-alone modern buildings on site.

Most of the older structures, converted to modern guest rooms, “had to be taken down to studs and re-clad,” Allen says. The dark college chapel with Tudor-esque engineered-wood arches was opened up with a wall of glass that looks out at new landscaping with water features; its new uninterrupted wood floors accommodate yoga classes. A run-down concrete-and-metal amphitheater amid the redwoods was fitted with new live-edge wood benches for transcendental meditation and “forest bathing.”

The freshly minted 1440 Multiversity opened in mid-2017. Since then more than 85,000 students have attended two- to five-day seminars led by a rotating faculty of thinkers, influencers and gurus. Denizens of Google and other tech firms come for philosophical leadership discussions with neuroscientists, artists and others. And for many, the place, with its creek and miles of hiking trails, creates a conduit to nature. “I have taken a number of classes now,” Scott says, for instance, learning meditation techniques from Neurosculpting Institute founder Lisa Wimberger, “to initiate relaxation responses.”

As the campus evolves, managing director Frank Ashmore, who has Ritz-Carlton expertise and a growing staff, is slowly turning 1440 Multiversity from a therapeutic commons to a multipurpose school/hotel/spa resort, complete with labyrinth and infinity-edge hot tub. A few tiered or free scholarships are offered for those unable to afford even the lowest-priced two-day $600 packages. Yet all lodgings have equally high-quality furnishings. Shareable two- bedrooms are available, as are Japanese-style eight-bunk dormitories in the basement of the new 5,000-square-foot auditorium completed in 2018.

Allen used a lot of salvaged and vintage materials for the sparely furnished interiors, with natural rock and driftwood accents. “It all evolved organically because nobody knew how big this project would get,” he says. “My job was to keep excess stuff out.”

IN SAUSALITO, another multipurpose project near completion may well absorb ideas from the others. In 2014, developer James To decided to refurbish the struggling Marin Theatre, on the quiet corner of Caledonia and Pine streets, a block from touristy Bridgeway. “I always look for underutilized buildings,” he says.

With the popular Sushi Ran, Bar Bocce and Joinery restaurants nearby, he envisioned a street-level tenant combining dining, music and movies, not unlike San Francisco’s Alamo Drafthouse or Mill Valley’s Lumber Yard, and offices upstairs, perhaps co-working spaces, in the long-unused loft.

For the development, called 101 Caledonia, he hired Ro/Rockett Design, a Sausalito/Los Angeles–based firm headed by college friend Jason Ro, to revamp the 1911 wood frame building. The company had never done a 14,000-square- foot commercial project before, but Ro, based in L.A., and Zac Rockett, his Sausalito partner and fellow alum of Harvard University Graduate School of Design, have worked on complex custom homes of similar scale in places like Aspen and Hong Kong and were up for the challenge.

As usual, they communicated digitally and by videoconference and “cross-utilized technology and each other’s teams,” Ro says. When Marin’s complex design review process made it seem that new theater tenants might not materialize, they decided to complete the office loft and leave the lower level undeveloped for a tenant to customize later. “This project is now just four walls and a roof,” Rockett says wryly.

But of course it is more than that. Even if the building may never again contain a movie house, it will have an anchoring street presence, fit “for any lively mixed-use tenant,” he says.

Such flexibility makes sense. The building has been many things before and will morph again. It began life as a Spanish Colonial Revival–style auto livery/garage and later became a venue for boxing matches, a single-screen cinema and, after 1992, a three-screen Cinemark theater with a lobby entrance on Caledonia. When it closed in 2016, “locals really missed that ‘public’ space,” Rockett says.

Because Sausalito is a former fishing village and a boat-builder had also used the top floor during the 1940s, the architects chose a nautical theme. They stripped the interior down to studs, and now the building’s remarkable heavy-timbered trusses holding up its gable roof — like the spars for a ship’s rigging — are revealed in the office space upstairs. Outside, vertical strips of rough-sawn cedar cladding are intended to echo a shipbuilder’s scaffolding. To take advantage of bay views, the designers eliminated sections of vertical screening at the office level and added a horizontal band of “lookout” windows for a belvedere.

“The cedar skin of the building is its soul,” Ro says — expensive to execute, but then again it’s hard to value-engineer a hand-built see-through screen.

The building they will unveil in early 2020 won’t be historicist but crisply modern, expressing its materiality like the work of their heroes Peter Zumthor and Le Corbusier, whose Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard Rockett knows well. The downstairs “clean slate” ideally will hold music or movie-related tenants. “I want it to be an entertainment and event space with a restaurant,” To says. “A gathering place for the community.” Rockett, who has worked on many wineries in the past, secretly hopes for a brewery or winery with a local culinary component. “The possibilities are endless,” he says.

This article originally appeared in Spaces’s print edition under the headline: “Come Together”.

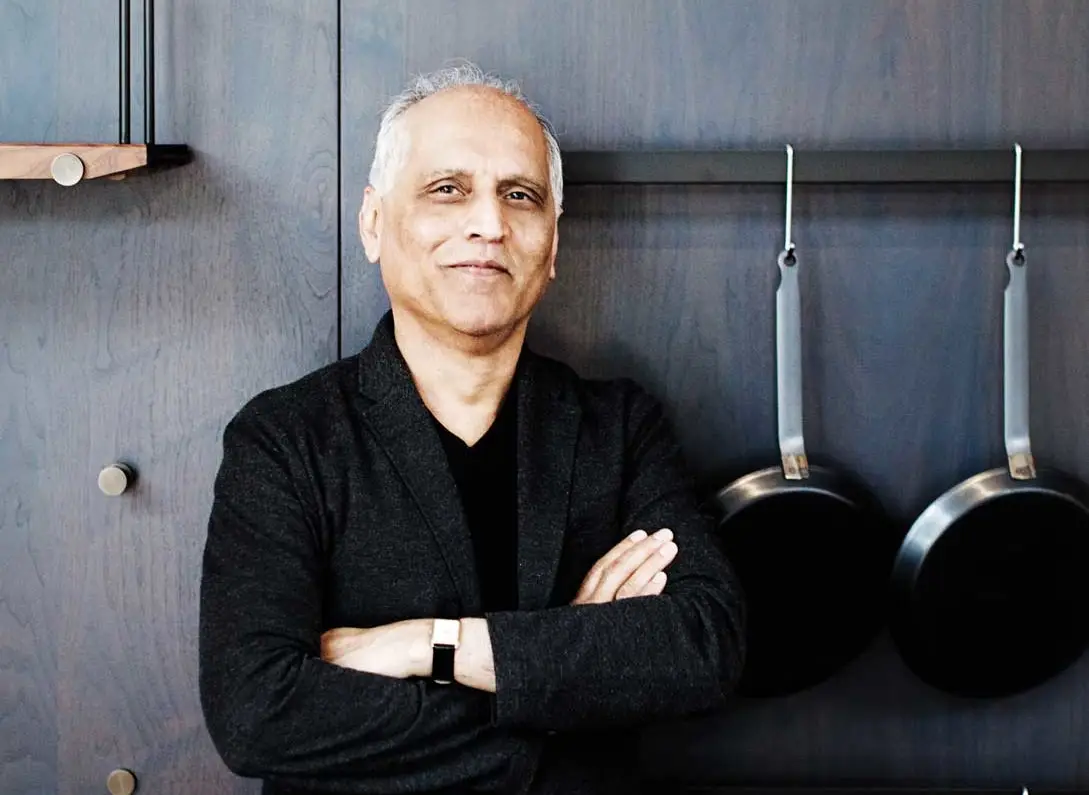

Editor-in-chief Zahid Sardar brings an extensive range of design interests and keen knowledge of Bay Area design culture to SPACES magazine. He is a San Francisco editor, curator and author specializing in global architecture, interiors, landscape and industrial design. His work has appeared in numerous design publications as well as the San Francisco Chronicle for which he served as an influential design editor for 22 years. Sardar serves on the San Francisco Decorator Showcase design advisory board.